At the heart of Bob Proctor’s teaching is a simple but unsettling claim: most people will live and die without ever truly living the way they want. The difference, he argues, lies not in luck or privilege, but in how we relate to purpose, time, and the hidden mental patterns that govern our lives.

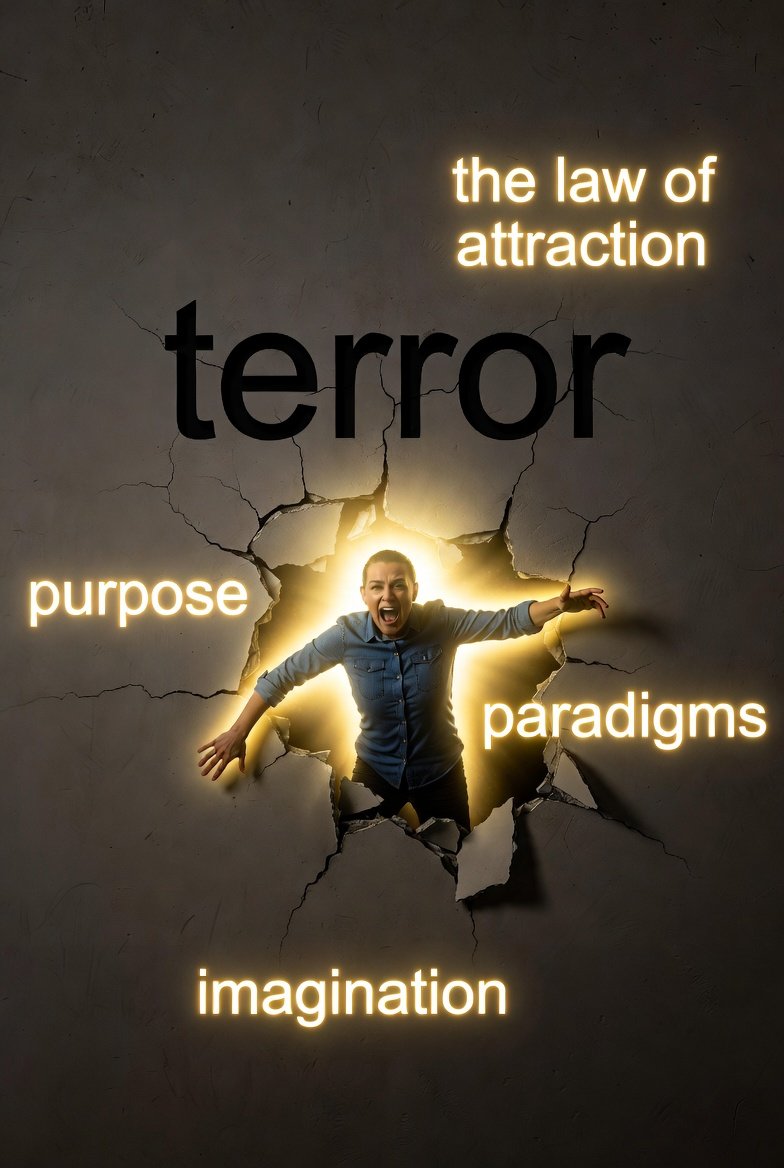

This article weaves together many of Proctor’s core ideas—purpose, paradigms, the law of attraction, imagination, and the “terror barrier”—to form a single message: anyone can radically change their life, but only by changing the way they think and act beneath the surface.

Purpose: Discovered, Not Decided

Proctor insists that purpose is not something we arbitrarily “decide,” but something we discover. “Determining” sounds like choosing from a menu; discovering implies uncovering what is already true about one’s nature.

He suggests a practical approach: repeatedly asking, in a quiet, undisturbed space, “What do I really love doing?” Not what pays the bills, not what others expect, but what one would gladly spend life doing. This may take months of consistent reflection, but he treats this as time extraordinarily well spent, because purpose becomes the core reason to get out of bed in the morning. Without this, work becomes mere obligation, and conformity (“doing what everybody’s doing”) becomes a kind of slow self-betrayal.

Time: The Sand in the Glass

To highlight the urgency of purpose, Proctor uses the image of a sand timer. The sand at the bottom is the past—unchangeable. The sand at the top is the future—unknown in quantity. No one knows how much is left. A grandmother who believed she was “soon to be gone” lived 34 more years; a 16‑year‑old friend died within minutes of what he assumed was a long future.

The only controllable zone is the narrow neck of the timer: the present moment, where the sand is actually falling. For Proctor, wasting minutes is not a small issue. He even translates time into money: at $50,000 a year, a minute has a measurable dollar value; at higher incomes, each idle half-hour becomes extremely expensive. The people who “win,” he argues, are those who refuse to squander minutes and instead choose deliberate, productive use of time aligned with their goals.

Rethinking Success

Proctor borrows Earl Nightingale’s classic definition: “Success is the progressive realization of a worthy ideal.” Success is not a static result (like “lots of money”) but an ongoing movement toward a meaningful goal. By this definition, someone like Mother Teresa, who did not pursue wealth, still counts as highly successful. Money may follow success, but it is not the essence of it.

This reframing reveals two major barriers: inner conditioning and outer environment.

Conditioning, Environment, and the Herd

From infancy, most people are conditioned—through family, culture, and early experiences—to adopt limiting beliefs about what is possible. They learn to speak one language and conclude that learning another is “too hard,” even though the brain is capable of far more. These ingrained patterns form what Proctor calls a “paradigm”: a cluster of habits, assumptions, and emotional set points stored in the subconscious mind.

Externally, people tend to copy those around them. They get jobs, look around, and do things as others do, rarely asking whether anyone actually knows what they’re doing. The problem, Proctor notes, is that statistics show about 95% of people never achieve financial independence or truly live the life they want, despite living in one of the richest societies in history. To imitate the majority, therefore, is to imitate failure.

The urge to “fit in” reinforces this: people fear making waves or standing out. Proctor contends that humans are not meant to live that way. We are meant to think independently, form our own aims, and allow our differences to express themselves in creative action.

Seeking Failure and Making Waves

Contrary to the “better safe than sorry” mantra, Proctor argues that safety kills growth. If someone is always playing it safe, they cannot discover how far they can go. He points to Thomas Edison, who framed his thousands of failed attempts at the light bulb as “3,000 steps” rather than failures, and to Sir Edmund Hillary, who failed on Everest multiple times before finally summiting in 1953.

What unites these figures is not the absence of failure, but a refusal to interpret failure as final. The idea of losing simply does not dominate their thinking. Proctor adopts the same attitude: he treats winning and losing neutrally, as part of the process. This emotional resilience opens the path to bold experimentation.

The Terror Barrier and Buyer’s Remorse

One of Proctor’s most powerful concepts is the “terror barrier.” It appears when a person entertains a “Y idea”—a new possibility beyond their familiar “X” pattern of living. This could be moving cities, changing careers, starting a business, or making a significant purchase aligned with a new identity.

While the idea remains purely intellectual, nothing changes. The moment someone becomes emotionally involved—truly commits—their nervous system shifts into a new “vibration.” Consciously, they experience doubt and fear; physically, that fear becomes anxiety. This is the terror barrier.

Most people, encountering this inner storm, retreat back to their old life. They cancel the move, back out of the sale, or talk themselves out of the risk. They feel relief because they’ve returned to what is familiar, even if it is deeply unsatisfying. This cycle explains buyer’s remorse, abandoned dreams, and lives lived in quiet frustration.

Proctor’s counsel is stark: unless one learns to pass through the terror barrier—acting in spite of fear—one will remain psychologically imprisoned, living as if there were a contract to live forever, postponing real change indefinitely.

Imagination, Self‑Image, and the Law of Attraction

For Proctor, imagination is the central creative faculty. Every modern convenience began as a mental concept in someone’s mind long before it existed physically. He claims that highly successful people mentally “step into” the version of themselves they intend to become and begin acting accordingly. (For those who don’t think in images, this can be understood as defining clear concepts, narratives, and behaviors that match the desired identity.)

He links this to the law of attraction: the idea that a person’s dominant mental and emotional states (“vibration”) draw in people, opportunities, and conditions that match them. But superficial positive thinking is not enough. The governing force is the paradigm, including one’s self‑image.

His example of weight loss illustrates this. A person whose self‑image is “overweight” can diet and temporarily lose weight, but if the inner image remains unchanged, the old weight returns—much like a thermostat pulling a room back to its programmed temperature. The same principle applies to income, performance, and relationships. To create lasting change, one must alter the inner “setting,” not just apply short‑term effort.

Living Deliberately

In essence, Proctor’s message is a call to radical responsibility. Purpose is to be discovered and lived. Time is finite and precious. Success is a path, not a prize. Growth requires thinking independently, seeking worthwhile failures, enduring the terror barrier, and reshaping deep mental patterns.

Behind all of this lies his core conviction: everyone has far more creative power than they realize, and the tragedy is not that life is harsh, but that so few people ever learn to claim that power and live on their own terms.